The work of Prof. Dr. L.W.J. Holleman

Exploring the Science of Alchemy in Life Processes

Goethean Scientific Paradigm: Learning from History

The previous article introduced two essential pieces of information: (1) the existing evidence is not good, and (2) practically all of it is way outside of anything conceivable by mainstream science. We are therefore left with two choices:

- To reject just about all the biological transmutation evidence as either erroneous, deluded or fraudulent,

- or, to develop a new scientific paradigm, in which such phenomena may be possible.

Paradigms

This article is not intended to be a review of the quality of the available evidence (this is for future articles). Its purpose is to explore the possibility of a new, philosophically rigorous scientific paradigm. The word paradigm has most recently been used to characterise how we view our life-world, our weltanschauung, our ways of thinking, doing, and ethics. To open mindedly consider a different paradigm is one of the most challenging tasks that we may undertake. It is a process involving the suspension of many of our most fundamentally held beliefs, of much of what we take for granted. For the majority of my life I have been entirely immersed in the mainstream scientific paradigm that has dominated all aspects of our modern world; social, political, and even the arts. Most of those who disagree with this paradigm, certainly those from academic circles, generally do so in terms of the very same paradigm they are trying to escape. Those who live or have lived mostly, or even entirely, outside of the mainstream paradigm are largely, if not entirely unintelligable to most mainstream scientists.

Historically there have been many alternatives to the mainstream scientific paradigm. Traditionally, the history of science is presented as the development of a simple linear process away from superstition and ignorance. Recent studies involving an entering into the paradigms of earlier times have in fact demonstrated that they were neither ignorant or deluded, within the context of their own time and place. It has also been found that most revolutionary scientific ideas were merely rediscoveries, or reworkings of pre-existing ideas. Therefore our search for an alternate or complimentary paradigm best suited for an understanding of biological transmutations requires an impartial consideration of several important paradigms in the history of science which will be conducted in the following article.

Scientific Paradigms

It is to Thomas Kuhn and his book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions

that we first turn to for guidance. By studying the history and philosophy of science he discovered that science works within networks of connected beliefs, values and techniques, that is, their ideas, theories, and ways of working were found to be internally coherent, and these he characterised as paradigms

. Normal science is practiced by a community of scientists who (almost exclusively) work within the one single paradigm. This means that they no longer have to explain everything that they do, or justify the foundations that underpin their every thought and deed, for that has already been done. The paradigm within which they work determines the scope of their observations. A good paradigm is usually robust enough to allow for minor modifications of theory to take place, so long as the foundations are not brought into question. By defining what is scientifically

acceptable, based on years of shared research experience, the chances of failure are reduced. Science is by nature a conservative activity, which to a large extent explains its reputation as the best means we have to certain knowledge.

A researcher's observations or theories that do not fit the scientific paradigm are considered, almost by definition, non-scientific. They are either accused of being either deluded or fraudulent, such as with cold fusion, or ignored, as is the case with biological transmutations. With the former, a modification or addition to the mainstream paradigm is all that is likely to be required. With the latter far more challenging case this is unlikely to be possible. A whole new paradigm is required.

Epistemology

Epistemology is a fancy word for the study of how we acquire knowledge. During the last half of the 20th century, philosophers of science came to accept that in practice science neither does not, nor could not work in the way it has been taught in our science textbooks. All observations have a point of point of view that limits how what is being observed is both perceived and conceived. Therefore knowledge is no longer about absolute facts that are either true or false; the methodology of the physical sciences is not the only means by which knowledge may be acquired. The challenge now in epistemology is to find new interpretations of the term relative

. Scientism and relativism characterise part of a stereotyped duality associated with that of objective certainty versus irrational subjectivity. This duality is known as the Cartesian duality as it was first clearly characterised, almost 400 years ago, by Descartes, and it has since become firmly established, especially within English speaking schools of philosophy and science.

Goethe and the New Science

Five years ago I wrote an essay of this title for a university course on the philosophy of history. I was interested in developing an understanding of how we can acquire knowledge without relying on such an objective/subjective duality. Such an epistemology will be required if we are to make sensible decisions in the development of our new revolutionary paradigm. I therefore present a slightly edited version below:

In 1725 Giambatista Vico published his groundbreaking work on an understanding of history, La Scienza Nuova. The aim of this essay is to demonstrate that the anti-Cartesian epistemology initially developed by Vico and presented in his The New Science is a particular case of a more general method for understanding implicit in the work of Johannes Wolfgang von Goethe. It will be shown that history, a branch of the humanities, requires a human centred science as a means to its understanding. Furthermore, since the nature of history is such that its characters are both created by and the creators of their historical environment, the past will be shown to be holistic in nature. To conclude this essay, the practical implications of working with a person centred

science and its complimentary nature regarding objective, mainstream science will be considered.

We Know What We Create

The central thesis of Vico's ideas may be summarised as follows1: Through our own efforts we have continually transformed both our immediate environment and ourselves. Also, as was pointed out by Descartes, our access to the external world differs in principle to that of our internal world. Vico, introducing here his verum factum principle, states that only that which we ourselves have created may be understood. Therefore, contrary to Descartes, we may only have certain knowledge of what are known as the humanities. History, since concerned with human actions that we ourselves create, is thus inherently knowable. Furthermore, we live, not as isolated individuals, but in societies, and possess what is known as culture. These are created, and are capable of being changed, by means of inter-subjective processes. They are therefore also inherently knowable. Their development is therefore not merely mechanical or causal. Vico further goes on to state that in order to understand the peoples of the past one needs to make the attempt to understand them in their own terms. This means that it is the particular rather than the general or universal that, according to Vico, should be the subject of what were later known as the social sciences. To summarise, we may quote from Isiah Berlin who states:

that therefore, in addition to the traditional categories of knowledge - a priori/deductive [fundamental mathematical truths such as 1+1=2, or tautological statements such asall single men are bachelors], a posteriori/empirical, provided by sense perception... - there must be added a new variety, the reconstructive imagination. This type of knowledge is yielded byenteringinto the mental life of other cultures, into a variety of outlooks and ways of life which only the activity of fantasia - imagination - makes possible.

Goethe and Vico

A comparison between Goethe and Vico was made by Caponigri2:

Goethe, reviewing the vast work of his artistic life, the poems, the plays and the novels which have made his name immortal, dismissed them as fragments. He was judging them, of course, in relation to the total vision which commanded his mind and imagination, upon which his spiritual eye was always fixed, but of which his compositions evoke but fleeting intimations. In this respect, there is a genuine affinity between Goethe and Vico.

This essay is an attempt to bring together some of the fragments of Goethe and Vico's ideas and to use contemporary philosophic thought to enable an understanding of their present-day significance.

Caponigri's quotation above on Goethe dismissing his life's work as an artist is, however, incomplete and illustrates a problem that has plagued Goethe both during his lifetime and ever since. Whilst Goethe is understandably famous for his poetry and plays, he also produced a large quantity of scientific work. It was his scientific rather than his literary studies that he hoped would become recognised as his greatest contribution to humanity. However, his scientific method only began to be taken seriously with the philosophical articulation of phenomenology and the rejection of a fully objective science in the last half of the twentieth century. Goethe's approach to developing an understanding of the natural world around him was phenomenological since his starting point was the direct unmediated experience of a given phenomenon, leading, by means of accurate description to more generalisable patterns, structures and meanings3. In a manner parallel to that of Vico before him, he sought a way to make himself open to the phenomena he was studying, to listen

to what they said

, so that their core aspects and qualities might reveal themselves to him.

Scientific Method

This may be contrasted with Kant in his Critique of Pure Reason4. Reason must approach nature with its principles... in one hand and with the experiment it has devised in accordance with those principles in the other, its aim, of course, is to learn from nature, although not in the capacity of a pupil... but rather in that of an appointed judge who requires the witness to answer the questions he puts to them.

This is a similar attitude to that of Francis Bacon5 nature exhibits herself more clearly under the trials and vexations of art than when left to herself

. Modern science has therefore been described - in somewhat emotive terms - as seeing nature as a woman compelled to answer questions when under torture with mechanical instruments. For Bacon, science becoming a means, not just for knowing the natural world, but also for having power and dominion over it, is the truly masculine birth of time.

By contrast, Goethe's phenomenological delicate empiricism

appears to be no more than naive romanticism6. Newton's success in combining Baconian empiricism with Cartesian rationalism produced an objective epistemology that remained essentially unquestioned for 300 years. Even today, despite or perhaps because of, Karl Popper's rigorous logical critique, objective, positivist science is generally considered to be the only means to truth

7. This is a problem for historians searching for the truth

about the past.

Objective Paradox

The underlying axioms of modern science assume the objects of study to be external to each other. If the nature of an object under study is wholly, or in part, determined by the objects that surround it, and these are in turn effected by the properties of the original object of study, the mechanism of cause and effect no longer holds true. Objectivity requires a cause to be prior to its effect; that which is effected cannot simultaneously play a part in its own cause. An experiment to test the premise that chickens are caused by eggs

, as opposed to the counter premise that eggs are caused by chickens

may be logically sound, but in reality it is a nonsensical joke. Yet, despite this obvious paradox, social scientists

8 still argue as to the priority of individual or society9. This problem of non-causal correlations is a familiar one in quantum physics and was the concern of the quantum physicist David Bohm10. He demonstrated that such problems may only be understood in terms of their being considered as coherent wholes. Henri Bortoft11, as a result of working under Bohm on the problem of wholeness in quantum physics, recognised in Goethe's science a way to a practical understanding of the concept of wholeness.

Hermeneutics

The example of the hermeneutic circle, though not one of Goethe's, is appropriate here as a starting point towards an understanding of holism. It was first recognised by Friedrich Ast in the 18th century, subsequently developed by Schleirmacher and more recently by Gadamer12. It is essentially the recognition of the circularity of an understanding of wholes and parts. To understand a text we have to read it, but to read it we have to understand it. It has been shown that the meaning of the whole is presenced

within the parts. As one proceeds in reading a text, our understanding of the whole reveals itself, in a similar way to that in which a photographic image progressively becomes intelligible with increasing image resolution. The process by which we attain this meaning is intuitive, using our faculty of imagination. Hermeneutics originated as a method for the interpretation of texts, especially the Bible. The importance of Gadamer lies in his realisation that all knowledge acquisition depends on interpretation. To interpret a text one has to understand its meaning. The meaning of a sentence is based on an understanding of its individual words whose meaning depends on their context (as anyone will know who has attempted to translate a foreign text with a dictionary). The words are patterns of ink on a page; they have a physical presence that are perceived by our physical senses. The conceptual meaning encapsulated by the sentence as a whole, though to be found in these printed words, is itself not a physical entity. It is an idea or concept that can only be seen with the mind's eye. It is discovered with the help of our faculty of imagination.

Social Knowledge

It is interesting to note that whilst the acquisition of meaning is not a linear, logical process, the conscious attempt to explain that process is. This is why we often believe that we understand something right up to the point where we have to explain it to someone else. It was this fundamental principle that was grasped by the later Wittgenstein13, after discovering Goethe's way of seeing, resulting in his subsequent split from the logical positivism of Bertrand Russel and Karl Popper14. In fact, as demonstrated by Wittgenstein in his Philosophical Investigations15, our private thoughts are expressed using public language. Therefore our subjective experiences, once cognised, become inter-subjective (shared personal experience). Thus all that we see requires some degree of interpretation, it requires our thinking, and since we express our thought in language that has its origins in social interaction, all scientific observations are seen through a filter of language, from a perspective of the scientist's particular cultural background. In fact, as Ziman16 has very clearly and succinctly explained,

the notion ofobjectivity, which looms so large in the philosophy of science, really means no more thanconsensual inter-subjectivity. There is no way of making an observation or arriving at an explanation that does not entail human perception and cognition;... [objective] science doesn't work, but in favourable circumstances it can be as true as anything is, in this mysterious world.

Therefore, if one is to preserve the concept of science

, its conventional meaning needs redefining to encompass its inter-subjective nature. Thus Ziman17 provisionally characterises academic science as a social institution devoted to the construction of a rational consensus of opinion over the widest possible field.

This inclusive approach enables the humanities

, including history, to be studied under the umbrella

of the sciences. The purpose for doing so would be in sympathy with the ideas of Goethe in his own scientific studies, namely to make one's methodological approach as exact and transparent as possible18, and that contrary to Popper a one method fits all

approach is not appropriate19.

Scientific Methods

Goethe's genius was to realise that one's scientific method should be adapted to the phenomena being studied. Rudolf Steiner20 discovered this as a result of being commissioned to compile and edit all of Goethe's scientific work. The subjects of study were broadly separated into inorganic

nature, organic

nature, and the humanities

, which included history, psychology, sociology, and other related disciplines.

Classical Physics

Where the objects under study are discrete physical objects, fully external to and independent of each other, the mechanism of cause and effect means that falsifiable predictions are possible and Popper's strict criteria for an objective science is possible.

Biology

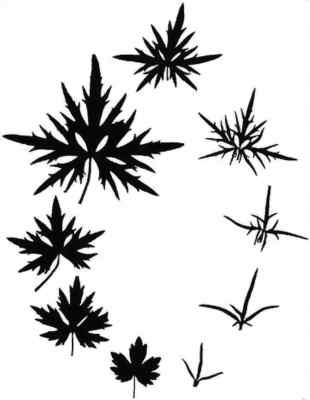

As Kant in his Critique of Aesthetic Judgement was aware, the parts of a living organism are not external to each other. However Goethe's studies of plant metamorphosis demonstrate that Kant's intuitive intellect is in fact possible. This may best be understood by means of a practical example. Consider the sequence of leaf shapes up the stem of a plant, the buttercup Ranunculus acris21 as shown here, is a good example.

If each of the leaves are cut out, mounted onto individual cards and the cards shuffled, even children find it an easy matter to reconstruct the original leaf sequence, missing leaves, or even leaves that have never existed but that belong to the plant just the same. The shape of each leaf relates to what Goethe characterised as the archetypal phenomenon

(Urphnomen). Analogous to that of Plato's ideal forms, it is that which contains the meaning of the whole form of the plant and which is accessible by an entering into the whole by way of the parts using what he called exakte sinnliche Phantasie (exact sensorial imagination).

Humanities

What we have here is the use of an imaginative faculty that remains true to the observed phenomena. This is the same faculty of exact imagination that Vico proposed in his New Science. There is, however a difference between a study of animals and plants and a study of, say, history. One might say that plants and animals are genetically pre-programmed. We ourselves, the subject of the humanities, are generally considered to be in possession of free will22. We are able to transcend our genetic heritage and our physical and social environments. Thus whilst a statistician may be able to make particular correlative assumptions, they can never be universal statements of fact.

Verstehen

As has been shown earlier in this essay, the approach to authentic understanding within the humanities is via a study of individuals using our empathic faculty of intuition. The Oxford Companion to the Mind23 reminds us that since almost all our judgements and behaviours are not based on formal logical argument, intuition is essential to our everyday lives.

Woman's intuitionis perhaps, largely the subtle use of almost subliminal cues in social situations from gestures, casual remarks, and knowledge of behaviour patterns and motives. Psychologists find these important matters for living almost impossible to formulate.

It is interesting to note that intuition here is an irrational activity associated, at least in English speaking cultures, with women. Empathic intuition is generally referred to as Verstehen, after its first use by Dilthey in history and Weber in the social sciences24 and subsequently in a revised form by Collingwood25.

Listening

The ethical challenges presented by the use of empathy are very clearly discussed by Rob Shields26. Empathy has, possibly naively, been used to mean the attempt to put oneself in the other's shoes

. However, with sensitive cross-cultural studies, speaking as

or speaking for

another from a culture outside of ones direct, personal experience can be morally controversial. Whereas in organic

nature there is a single unifying idea, in the humanities there are a multiplicity of meanings and possible understandings, for in each meeting of individual minds something new can arise. Shield's solution for sociologists (as well as for historians) was that of the dialogism

of Mikhail Bakhtin27. In every day experience, conversing with another helps us to understand and bring new meaning to our own personal experiences. An authentic conversation or dialogue is essentially an alternating process of observation

(selfless listening) and reflection

, by means of our reconstructive imagination. A recognition that in human affairs a multiplicity of meanings and understandings is always possible is an essential part of this process. Goethe's writings on the nature and practice of conversation has been collected and interpreted by Marjorie Spock28. It must be stressed that this essentially hermeneutic process of dialogue is not the same as the dialectic of Hegel, which along with German Idealism in general, was severely criticised by Goethe29.

Studying History

To conclude, between an objective

physical science and the subjective

arts are to be found the humanities, which include the study of history. It has been shown that historians seeking to understand their past are able to do so by means of a philosophically sound scientific epistemology that was first recognised by Vico in his New Science and which is implicit in the scientific ideas of Goethe. This proposal has been supported by twentieth century philosophical advances, especially in the fields of phenomenology, hermeneutics, and linguistics.

The Goethean Paradigm

I hope that the above has given something of an introduction to what has become known as Goethean science

. I also hope that this has given sound philosophical reasons as to why both myself and Holleman wished Goethean science to be the foundation of our research.

Notes

1. Isaiah Berlin, Three Critics of the Enlightenment: Vico, Hamann, Herder (2000), pp. 8-12.

2. A. Robert Caponigri, Time and Idea: The Theory of History in Giambatista Vico (1968), p. 202.

3. David Seamon, 'Goethe, Nature, and Phenomenology: An Introduction' in David Seamon and Arthur Zajonc, eds., Goethe's Way of Science: A Phenomenology of Nature (1998), p. 1.

4. Cited in H. B. Nisbet, Goethe and the Scientific Tradition (1972), p. 35.

5. Cited in Henri Bortoft, The Wholeness of Nature: Goethe's Way Toward a Science of Conscious Participation in Nature (1996), p. 243.

6. Ibid.

7.See, Donald Gillies, Philosophy of science in the twentieth century: four central themes (1993). See also, Alun Munslow, The Routledge Companion to Historical Studies (2000/2002), pp. 215-219.

8. By social scientists

it is meant those who work - historians, sociologists, psychologists - in the middle ground between the physical sciences and the creative arts. This matter is discussed more thoroughly later in this essay.

9. Michael Stanford, An Introduction to the Philosophy of History (1998), pp. 120-121.

10. David Bohm, Wholeness and the Implicate Order (1980/1995), pp. ix-xv, 129-139, 143-157, 172-179.

11. Ibid., pp. ix-xi.

12. Hans-Georg Gadamer, 'On the Circle of Understanding' in John M. Connolly and Thomas Keutner, eds., Hermeneutics versus Science? (1988), pp. 68-78. See also Conolly and Keutner in their introduction, op. cit., pp. 1-67. For an easier interpretation see Bortoft, op. cit./ pp. 7-9.

13. Bortoft, op. cit., pp. 399-400.

14. Gillie, op. cit.

15. Ibid.

16. John Ziman, An Introduction to Science Studies: The Philosophical and Social Aspects of Science and Technology (1984/1998), pp. 35-37, 109-110.

17. Ibid., p. 10.

18. Dennis L. Sepper, Goethe Contra Newton (1988), pp. 43-45, 62-63, 65-79.

19. This matter cannot be stressed strongly enough; the philosophical foundations of an objective

science have been demonstrated to be grossly inadequate in the past few decades. Consequently, either the vast majority of so called scientific

fields of study need to lose the epithet of science, or the definition of science needs to be broadened beyond that of naive objectivity.

20. Rudolf Steiner, The Science of Knowing: Outline of an Epistemology Implicit in the Goethean World View With Particular Reference to Schiller (1924/1979), pp. 14-16, 18-19, 22-27, 75ff., 84ff., 101ff.

21. Ronald H. Brady, 'The Idea in Nature: Rereading Goethe's Organics' in Seamon and Zajonc, op. cit., p. 94.

22. Chris Horner and Emrys Westacott, Thinking through philosophy : an introduction (2000).

23. Richard L. Gregory and O. L. Zangwill, eds., The Oxford Companion to the Mind (1987), p. 389.

24. Stanford, op. cit., pp. 176-177.

25. Munslow, op. cit., pp. 47-49.

26. Rob Shields, 'Meeting or Mis-meeting? The dialogical challenge to Verstehen' British Journal of Sociology, 47 (1996), pp. 275-294.

27. M. M. Bakhtin, The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays, ed. Michael Holquist (1981/1998), p. 426.

28. Marjorie Spock, 'The Art of Goethean Conversation' in, The Green Snake and the Beautiful Lily: Johann Wolfgang von Goethe's Fairy Tale (1999).

29. Arthur Zajonc, 'Goethe and the Science of His Time' in Seamon and Zajonc, op. cit., pp. 18-20.